Carbohydrates improve performance during long-term exertion (> 2h). Proper fluid consumption can help prevent severe dehydration as well as contribute to better performance. However, many people have a problem with the answer to the question: is it best to drink energy drinks, gels, eat bars, or maybe bananas or other sources of carbohydrates? During long-distance races, athletes seem to make different choices. We see exercisers with drinks, some prefer gels, and others can eat classic sweets! To answer the question of what to choose, the researchers conducted a series of studies on University of Birmingham.

Overview of study

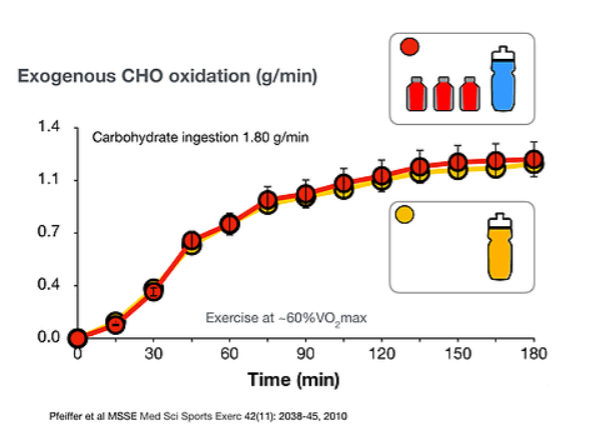

The research was part of Beate Pfeiffer's doctoral studies. In the first study (1) she compared the consumption of a sports drink with the consumption of a gel containing the same amount of carbohydrates and water. The cyclist rode for moderate intensity for two hours and consumed 1 gel per hour (with a 2: 1 ratio of glucose: fructose) with 200 ml of water or a carbohydrate drink. In both trials, cyclists received the same amount of carbohydrates. The average carbohydrate intake was high: 1.8 g / min + liquid intake. Carbohydrates were "labeled" with carbon-13, which allowed Beate to calculate how many carbohydrates were consumed during exercise. In the above figure, exogenous carbohydrate oxidation (how much carbohydrate was used) was presented for two trials and it is clear that there were no physiological significant differences between the two forms of carbohydrate intake.

This is not surprising, because in one case the carbohydrate is mixed with water in the bottle, and in the other case the carbohydrate gel is consumed and mixed with the water in the stomach. The carbohydrate concentrations are the same and this means that the carbohydrate supply must be very similar. The bottom line is that it does not matter if the carbohydrate is supplied as a sports drink or as a gel with water. Note: if the gel is consumed without water, the content in the stomach will be strongly concentrated, which will slow the gastric emptying, and more likely will cause gastrointestinal problems.

Drinks or energy bars?

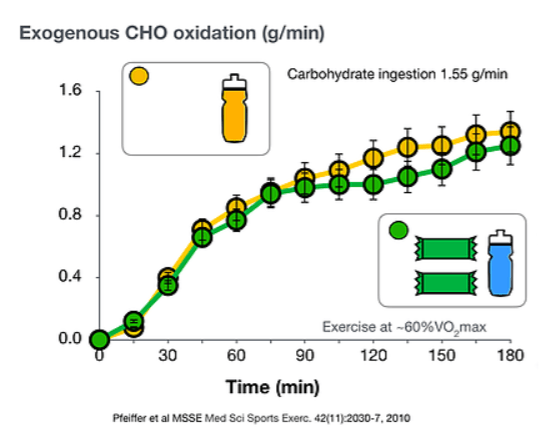

In the second study (2), the energy bar was compared to the carbohydrate drink. The design of the study was very similar: the cyclist drove two hours again and this time they received a carbohydrate drink or energy bar with water. The total amount of carbohydrates consumed and the total amount of liquid consumed was matched in two attempts. The bar used in this study was a widely available energy bar with high carbohydrate content, but low in protein, fat and fiber. The results of this study are presented in the figure above. Also here the difference between solid food and water and carbohydrate drink is small and statistically completely irrelevant. Using carbohydrates from a bar seems a bit worse, but the difference is small. It is very likely that this is because this one

the specific product has a very low level of fat, protein and fiber. An energy bar with a higher fat, protein and fiber content will probably slow gastric emptying and reduce the supply of carbohydrates.

As the results of these two studies show, the form of carbohydrate intake is of little importance for the oxidation of carbohydrates. In other words, as an athlete, you can mix and match and use gels, bars or sports drinks at will or whatever you prefer to take carbohydrates during exercise. In terms of providing a fluid that has not been tested in this particular study, one would expect that, when providing solid foods, we would consider it less. Athletes can therefore combine and match any source that best suits their individual preferences. Some athletes prefer liquids, others really need to eat something to survive longer races in good form. For some athletes, gels are a convenient way to take carbohydrates, but not everyone is their fan. So choose the carbohydrate source that suits you. Work out the goal and plan your nutrition properly during the race!

References: