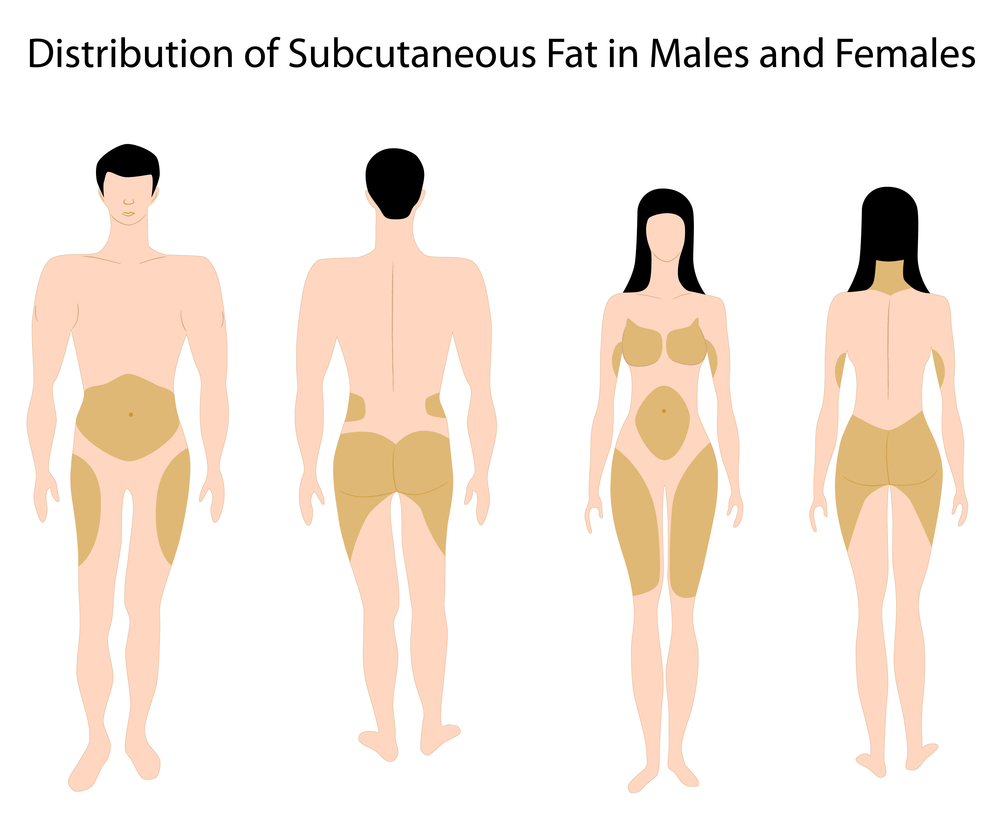

Everyone has some body fat. Healthy levels of body fat actually improve a person's health and appearance, but excess fat tends to increase the risk of poor health and is generally viewed as unattractive in most cultures. Excess fat accumulates in different areas from person to person, though some generalities can be made. Women tend to accumulate fat in the thighs and around the pelvis (hips, buttocks and the lower abdominal) men are more likely to deposit body fat in their midsection, providing a visual cascade of fat over the restraints of stressed belts. This have given rise to the descriptive terms of apple-versus pear-shaped body types.

Fat distribution

Apples shape can include both men and women. Abdominal fat, both visceral- surrounding the internal organs and subcutaneous- under the skin, accumulates due to a state described as glucose intolerance or insulin resistance.

Why are we getting fatter?

Glucose is scientific term for sugar in its most common form. Glucose is in nearly every carbohydrate-containing food and is the main stimulus for insulin secretion. Most lean people are very efficient in dealing with glucose, using only the necessary amount of insulin to shuttle the sugar molecules into the muscle, liver and fat cells are the main targets. However, some people become resistant to the insulin signal, so the pancreas releases more of the hormone into the bloodstream in order to dispose of the sugar influx from a meal. In some cases, insulin remains high, even when the person is fasting; others have normal fasting insulin but have to release a great deal more of the hormone when food is consumed. Fasting is the state of the body when one has not eaten for several hours.

It is important to realize that all carbohydrate-containing foods are not the same. Some dump their sugar load into the bloodstream rapidly, causing sudden fluctuations in serum glucose levels. This causes the pancreas to respond by pumping out large amounts of insulin - examples include white bread, most breakfast cereals, and sugary drinks. Other foods release their sugar load slowly, allowing the pancreas to deal with the sugar influx gradually by releasing smaller amounts of insulin over a longer period of time - examples of these foods include milk, yogurt and most types of beans.

How quickly the sugar from a food reaches the bloodstream determines its glycemic index. However, the glycemic index is not the complete solution to weight loss and managing insulin. The total amount of carbohydrate consumed needs to be accounted for as well - total carbohydrate content x glycemic index = glycemic load. When a high level of insulin is released after a meal, it promotes fat gain because insulin blocks the release of stored fat, promotes fat storage and causes blood glucose to plummet. When fats are shuttled away and blood sugar drops, hunger signals are generated and a person tends to overeat, consuming more food and eating more frequently. People who experience a moderate release of insulin following a meal tend to avoid the metabolic mismatch and generally experience greater success in managing their weight. Controlling the glycemic load of a meal is one way to control the insulin release after a meal. People who release a lot of insulin after a meal would lose more weight following a low-glycemic-load diet.

Clinical study

Two groups of people were randomly placed into either a low-fat diet program (55 percent carbohydrate, 20 percent fat, 25 percent protein) or an identical program using a low-glycemic-load diet (40 percent low-glycemic-load carbohydrate, 35 percent fat, 25 percent protein). People follow this diet for 18 months. Among the many subjects, most (75 percent) had normal insulin release, which was measured by testing blood insulin levels 30 minutes after drinking a sugary drink containing 75 grams of glucose. However, 25 percent released more insulin than their counterparts.

The total group of all subjects lost approximately the same amount of weight, regardless of type of diet consumed. However, when the data among the high-insulin releasers were analysed separately, it became clear that one of the diets was superior for producing fat loss and possibly improving cardiovascular health. Among this 25 percent, containing the high-insulin releasers, the low-glycemic-load diet resulted in a greater loss of body fat (nearly triple). The lipid profile, a measure of cardiovascular risk, was better among the subjects on the low-glycemic-load diet as well, with higher "good" cholesterol (HDL) and lower triglycerides (blood fats).

Results

The value of this study and the findings are very important to the general public, as overweight and obese people make the great majority of the adult population and many are insulin resistant. However, for athletes who typically maintain a lower body fat and generally have a healthy insulin sensitivity profile, the value of the findings is less certain. Athletes and bodybuilders seek every advantage to maximize the positive results of their training and diet, it would appear that utilizing a low-glycemic diet during periods when fat reduction is the primary goal would be beneficial.